Sarvangasana - Shoulderstand

Etymology and Synonyms

Sarvanga (सर्वाङ्ग sarvāṅga): entire or perfect in limb, complete, whole body, all the limbs, all the vedangas वेदाङ्ग.

Introduction

This posture, the “posture of the whole body” is called shoulder stand as it integrates the set of “inverted positions” (positions that raise the body above the head. Those positions are named viparītakaraṇāsana. This term is broken down into two terms, viparīta and karaṇāsana. The determined term karaṇāsana is further broken down into āsana (a posture) and karaṇa meaning “the one who acts, the practitioner”. The determined term is therefore translated as “posture of the practitioner.” The determining term viparīta is built on the verbal root I- (to go) augmented by the prefix pari (around) and vi which marks a deviation or an inversion. Viparīta is therefore translated literally as “that which goes back, which goes in the inversed direction” and the complete expression viparītakaraṇāsana is then “inverted posture of the practitioner”.

Āsana

In the final attitude, the body rests upon the shoulders and the nape of the neck—which accounts for the posture's English name—shoulder-stand.

First Phase

Lying flat on the back, the back is flattened as much as possible. Then, flatten the curve of the neck by moving the chin towards the sternal fork.

Bring the legs up to the vertical position. The muscles of the lower limbs are minimally contracted: the muscles of the legs, feet and toes are not contracted. The lower back curve is flattened as much as possible. This reduces undue strain on the fifth lumbar vertebra and its disc.

If there is too much strain in raising the legs straight, or if there is pain or strain at the level of the lower back, the knees should be bent before the feet are raised. By contracting the abdomen, raise the legs very slowly. The upward movement is slow and steady.

The face and arms are relaxed. Breathe calmly and evenly; do not hold the breath.

Raising the Legs and lower trunk to the Vertical Position

The legs continue to go upward, through a contraction of the abdominal muscles and, if necessary, by the help of the hands.

In the ascending motion of the legs, attention is paid to apply a continuous elevation of the different sections of the back, starting with the sacrum, lower back and middle back. The muscles unnecessary to the position are kept relaxed. The practitioner keeps an inner awareness of those of the neck, face, shoulders and feet.

The feet and knees are kept together. In the final position, the hands push up and support the back resting at the level of the lower ribs, elbows touching the carpet, and forearms propping up the body so as to keep it vertical. The sternum rises to rest against the chin, and the nape is flat to the floor.

In the ideal position, the trunk and legs are lined up vertically and the base is the beginning of the neck, exactly around the cervical vertebra C7. In the intermediary stages, the muscles of the upper thoracic and cervical spine have not reached a length permitting the position. Therefore, in the intermediary stages, what matter is to reach a level of comfort, balance and minimal contraction of the muscles. This is achieved by having the back slightly rounded and the legs slightly bent or slightly tilting away from the vertical. In this position, the curve of the back and the tilting of the legs create two compensating vectors cancelling exactly at the level of C7, thus achieving the balance.

The final position is realized when the trunk and lower limbs are near vertical. In this position, the upper limbs raised vertically or the arms are on the grounds, forearms raised and hands supporting the flanks. In this second situation, the fingers can be used to exert specific pressure points or zones on the trunk. For example, the practitioner may want to induce an activation of specific shu or mu points (i.e. LU1).

Returning to the Ground

The return consists in following exactly the movements taken to assume the posture, but in the reverse order. Each stage is controlled to ensure a smooth flow, the head remains on the ground and the muscles non-necessary to the return are kept relaxed. The spinal column should uncoil progressively from nape to sacrum.

For Beginners

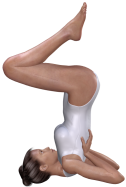

In the initial stages of a yoga practice, or after recovering from illness or trauma, a practitioner may choose ardha-sarvāṅgāsana (the half-shoulder-stand). In this the legs should be raised perpendicularly as before; then try to lift the trunk is lifted near vertical and supported by the hands under the buttocks, bending the knees to assume the position as illustrated in Figure 2. Then practice the inner dynamic works.

Figure 2 - Half-shoulder-stand.

Pranayama

In the inner dynamic stage, the practitioner focuses on the diaphragmatic and mid-intercostal breathing while observing the effects of the immobilization of the upper rib cages on the prevention of upper breathing. The aim is to obtain smooth inspiration and expiration and to expend the rib cages laterally while noticing the sensations generated. As for all breathing, the frequency needs to be insured, either by counting or by synchronizing with the heart beats. This second method, which comes naturally as the practitioners starts perceiving his or her heart beat is preferable as it introduces a coupling between heart rate and respiratory rate.

Pratyāhara - dhāraṇā

In the final position, the focus is first on relaxing the various muscles that may tend to tense. Then the focus is on balance and on insuring a distribution of weight at the level of the nape, focusing on the contact nodes, such as C7, T1, occipital contact zone and shoulders. Then, the visualization goes into the observation of the regions being stretched (posterior compartment of the neck) and the regions being compressed (anterior compartments of the neck). Finally, the observation extends on the feelings generated in the diaphragmatic and visceral areas during the regulating breathing.

Once these steps are achieved, the practitioner moves into the visualization of the activation of the lines or energy being stimulated through this position, namely the neck and upper back pathways of the Bladder and Gallbladder meridians.

Incorrect Positions

Among others,

1. Do not work in jerks.

2. Do not kick off to reach the vertical position: if you find this impossible, then use a wall to help you, and place the hands under the buttocks, or, alternatively, approach the posture by way of a half Sarvāṅgāsana (see Figure 2). The chin should rest on the chest; the nape of the neck should be laid flat on the floor in the final position.

4. Do not fall heavily without controlling your return to the ground.

5. During your return, do not let your head leave the ground, which it touches throughout the exercise.

6. Do not separate the legs; feet and knees should stay together while the posture is being taken up or is being released. An exception would be in raising or lowering one leg at a time as an alternative if the abdominal muscles are weak, or in case of inguinal pathologies.

7. Insure that the chin lock is maintained at all time.

8. Do not get up suddenly when the posture is over. Allow the blood pressure to stabilize first.

Contraindications

Inverted positions should be avoided in the following cases: pathologies of the spines, severe hypertension, glaucoma, dental abscess, ear infections, sinusitis, fever, thyroid pathologies, sclerosis of the blood vessels of the brain, etc.

Effects

Effects common to inverted positions

1. Improvement in the circulation of the blood (legs, stomach).

2. Decongestion of the organs in the lower part of the stomach with relief from hemorrhoids.

3. Relief in ptosis or prolapse (of kidneys, stomach, intestines, uterus).

4. Improvement in the flow of blood to the brain.

Spinal Column and muscles

Sarvāṅgāsana has a specific effect on the upper thoracic and cervical spine and associated muscles through the hyperflexion of the cervical and upper thoracic vertebra. The positioning of the spine in sarvāṅgāsana and halāsana creates a posterior spinal decompression stretch specific to cervical and upper thoracic vertebra.

The Brain and Nervous System

Sarvāṅgāsana and halāsana acts upon the cervical and upper thoracic section of the spinal architecture. Additionally, as all inverted positions, it introduces a modification of blood circulation in the brain. Increased blood circulation in the brain is suggested to increase oxygenation and nourishment of brain structures. There are however no adequate studies to negate or support improved mental functions.[1] Finally, the cervical spinal nerve roots are stimulated through both stretching and increased blood flow.

Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

The yoga literature and community is supporting the belief that Sarvangasana exerts a profound influence on the functions of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The supportive rational is based on the modification of the blood supply in the neck occurring in the position. Based on this belief, there is an increased blood supply to these glands, thus normalization of their functions.

Breathing

The sternum-chin lock prevents upper thoracic breathing, limits middle thoracic breathing and accentuates diaphragmatic movements. Additionally, the diaphragmatic breathing is characterized by working under gravity inversion.

Note: Postural drainage reported with inverted positions promotes expectoration of sputum in conditions such as chronic non-tuberculous lung infection,[2] bronchiectasis[3] and asthma.

In upward thoracic positions gravity pulls the fluids downward and blood “perfuses” or saturates the lower lungs more thoroughly. In inverted positions, the blood perfuses the upper lobes of the lungs.

Circulation

The general circulatory effects of inverted postures rest upon gravity inversion. They include promotion of the venous return and lymph drainage in the lower limbs. However, such effects are associated with increased retinal pressure and the posture should therefore be avoided in retinal pathologies.

The Abdominal Organs

As for circulation, the general abdominal effects of inverted postures rest upon gravity inversion. It is suggested that the effects include improvement of ptosis and prolapse, visceral blood stases, and reduction of circulatory congestions in the lower abdomen.

Skin

Blood supply to the face and scalp increases during the posture and the classics suggest improvement of wrinkles.

References

[1] Kimbrough et al found that inverted positions have no effects on short-term memory. They study design is of great interest in the evaluation of effects of inverted positions. See Kimbrough et al in The effect of Inverted Yoga Positions on Short-term Memory. The Inline Journal of Sport Psychology. 2007. 9(2).

[1] Minnesota Medicine. Volume III, January to December 1920. P. 356

[1] Stevens, A. The practice of Medicine. W.B. Saunders Company. 1922. P. 578.